Archive

12 Books Read in 2022:

1. Singapore Swing, John Malathronas, Summersdale, 2007, 318pp

I read this book as I’d been in Singapore in the past. Quite likeable, but including too many Buddhist myths: 2 stars.

2. Lion and the Unicorn – Gladstone v Disraeli, Richard Aldous, Pimlico, 2007, 368pp

I’ve been to Gladstones Library in North Wales several times, so this was an interesting book to read. It’s hard to work out who came out on top, as these men had both strengths and weaknesses. However, this is a great book and well worth reading: 5 stars.

3. A Field Guide to the British, Sarah Lyall, Quercus, 2008, 277pp

The author is American, and I’d recently read a book by her husband, Robert McCrum, ‘Every Third Thought’, about his stroke in London (very good). However, this book looks at the many differences between the UK and America. Quite interesting: 3 stars.

4. Conclave, Robert Harris, Penguin, 2017, 380pp

This is one of my favourite authors. This book is good, and I enjoyed it very much. It basically looks at ‘power’ in the Catholic Church as the Cardinals choose their next Pope. Definitely worth reading: 4 stars.

5. Prisoners of Geography, Tim Marshall, Elliott and Thompson, 2016, 304pp

An excellent author. I came to read this book quite late, but it is so good. It looks at ten regions and countries around the world, including Russia. I learnt so much from it. Do read it: 5 stars.

6. Crete (Travel), Fisher and Garvey, Rough Guides, 2022, 380pp

7. Crete (Travel), Marco Polo, 2018, 156pp

We visited Crete last year. These are the two books we took with us. Both very good: 4 stars.

8. Operation Mincemeat, Ben Macintyre, Bloomsbury, 2010, 414pp

Another good author – I love what he writes. This book looks at an Allied attempt at fooling the Germans in WW2. Good film too. It’s set in Spain, and apparently it changed the course of the war. Somewhat of an unbelievable plot, but it seemed to work: 4 stars.

9. Power of Geography, Tim Marshall, Elliott and Thompson, 2021, 380pp

More Tim Marshall, and more regions/countries of the world including ‘Space’ as well. Again, I learnt so much from reading this book. Please get one yourself, it’s very good: 5 stars.

10. Crossways, Guy Stagg, Picador, 2018, 416pp

An interesting author, and for Guy, this was a ‘secular’ pilgrimage as he’s a practising non-believer. Guy walked across Europe, through Turkey and he finished in Jerusalem, Israel. I heard him speak recently and enjoyed what he said. I like this book, and he is quite open about all that he saw en-route. A very useful book, and I hope you enjoy a good read too: 4 stars.

11. A303 – Highway to the Sun, Tom Fort, Simon and Schuster, 2019, 355pp

I live in the South-West of England now, and use this road quite frequently. It’s a much better road that the M4. This is an excellent book, and I really enjoyed reading it: 5 stars.

12. Andalucia and Gibraltar (Travel), Noble and Forsyth, Lonely Planet, 1999, 440pp

We visited Spain at the end of last year. This was a helpful book, although it was the first printing: 4 stars.

Review – ‘The Face Pressed Against a Window – The Bookseller Who Built Waterstones’.

This is a fine book, particularly if you want to know more about how ‘Waterstone’s the Bookseller’ was built. Waterstones is a great business, and despite many earlier difficulties, it continues to be very good at its business. I do trust that this will continue well into the future.

The book is well written, and the author is keen to speak quite a lot about his own background before the growth of Waterstone’s. I don’t think I’d realised before, but the Waterstone’s book chain was being established from 1982-1993, whilst I was at STL Distribution in Carlisle, Cumbria.

In my view, Sir Tim (81) is first a businessman and then a bookseller. However, his bookshops are extremely good, and have stood the test of time for a very long while. Tim sold Waterstone’s to WH Smith’s eleven years later (they had sacked him previously). Wonderful!

Happily, Sir Tim Waterstone gave me a foreword to my own book on ‘Your Christian Bookshop – A Complete Resource’ (Jay Books) in 1992. I was clearly aware of him, but I had no idea that Waterstones would become the extensive business that now covers the whole of our country.

He says in the foreword, ‘I believe that the world of Christian bookselling is ready to go through the same revolution that general bookselling has been going through in the last few years. There is nothing to fear’.

Tim’s book is in two parts. Firstly, there is the overview of his own life – from his childhood in Crowborough (he didn’t get on with his own father at all), as a colonial boarder in Warden House, onto Hawkeshurst Court and then to Tonbridge School. Onwards to St Catharine’s College in Cambridge, and then some time in India to join a Calcutta broking firm, before then embarking on his own Bookshop chain, Waterstone’s.

During this time in India, Tim married but in a few years this marriage broke up. However, Tim says really nothing in the book about this time, and actually later on, the same happens again – and again nothing is said. Between all of this, Tim had a depressive breakdown, but fortunately this did not occur ever again.

The second part of the book looks at how Tim started Waterstone’s. On returning from India, Tim joined Allied Breweries followed by WH Smith. Whilst in America, working on behalf of WH Smith’s, he was dismissed by the WHS Chairman who apparently said to him, ‘We don’t really mind what you do now, though we wouldn’t want you to go straight out and open a load of bookshops in competition with us. That we would stop! Tim writes, ‘I was angry, but at the same time I was exhilarated’.

The idea that stood out for me was just how much time he had put into growing his own Bookshop business. It was clearly part of him. Sir Tim had been looking at this idea for a long time before starting the business in 1982.

Initially, Waterstone’s was actually a ‘rollercoaster ride’ and Tim put in a lot of his own money in those early days. He was able to obtain bank lending at a time when retail was doing very well (there was no Amazon, for example), and Tim knew exactly what he wanted from his own Book chain.

His mantra was ‘perfect stock, perfect staff, perfect control’.

I guess he sold it at time when a number of factors were coming into retail, which ultimately affected how, good or bad, these businesses would become. Following that first sale to WH Smith, Waterstones went through a 10 year period – under HMV Media – when it really struggled. Tim was part of this till 2001, and eventually he had to stand down, upset by all that was happening around him.

Ultimately, in 2011, Tim became the Chairman of the new company with James Daunt as CEO, and owned by the Russian billionaire, Alexander Mamut. Interestingly, Tim still speaks very lovingly about Waterstones as a business, and his comments – now – about the Elliott Advisors involvement in the business are very illuminating (p273).

I wish Waterstones well. They have an excellent brand, and many book lovers would generally buy from them, as opposed to Amazon. Most UK towns and cities have a Waterstones present, and I trust that this will be the case for a long while yet.

——————————————————————————————————————-

The Face Pressed Against a Window – The Bookseller Who Built Waterstones

Sir Tim Waterstone

323pp, 2019, Atlantic Books

ISBN: 978-1-78649-634-4

Review – ‘In the Days of Rain’ by Rebecca Stott.

This is a brilliant book.

The Times reviewer described it as ‘compassionate and furious’ and ‘an intense accomplishment’. I truly enjoyed it. It helped me understand some of what happened in my own family in the Exclusive Brethren in the 1960s. No one really told me very much about it all.

I have three older brothers, and I am the youngest in our family. I’m not sure that being in the Brethren really bothered me too much. By then, we had left the ‘Exclusive’ Brethren and had gone to another church in Oxfordshire in 1963. I guess this church was still Brethren in character, but some of the wider practices had been put aside by people, including my parents, who did not agree with such terrible concepts.

However, for my eldest brother this was not really true, and for a number of reasons he walked away from Christianity. I have thought much about this throughout my life and recognise why he did this. Overall, the Exclusive Brethren was a cruel system, and if you did not agree with the way they worked, then it would be very bad for you – and my brother was in that category. I do not blame him for this at all.

The author, Rebecca Stott, was born in 1964 – 7 years after me! She is currently Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia, UK. Rebecca is also an historian and wrote this book, In the Days of Rain: A Daughter, A Father, A Cult, in 2017. The book won the 2017 Costa Book Award. She has three grown up children, Jacob, Hannah and Kezia, and lives in Norwich.

Rebecca writes well, and she is very articulate. Her family went back over four generations – over 100 years – in the Plymouth Brethren, and her grandfather was a trustee of the Stow Hill Bible and Tract Depot, near Brighton. Her father also did well, and preached in many countries, ministering for the Exclusive Brethren. Initially the Plymouth Brethren were ‘just good men walking in the Lord together, trying to find a way of living according to Paul’s gospel’. Later it all went very wrong ……

The Exclusive Brethren ‘collapsed’ in July 1970. This happened in Aberdeen, Scotland and caused ructions across the world. J.T. Taylor Junior, the Brethren ‘Man of God’, slept with a married woman in Scotland, and it was this that caused a separation of ways within the Brethren. It split the worldwide movement right down the middle.

However, there are still 45,000 Exclusive Brethren across the world, 16,000 of them in the UK. That’s a lot of people. This sect is still here, ‘they blend in’, and now is even on the Internet!

The book details how when the family left, it all came to a shuddering halt. Her father ended up going to prison due to gambling debts. When he came out he worked at the BBC for a while, but again his gambling caught up with him, and he ended his days in Norfolk completely going against any of the Christian teachings which he himself had preached years before. All in all, an appalling and sad tale.

Rebecca herself ‘came out’ from the Exclusive Brethren with her family but clearly looking back on it, understands a lot about what was being taught. She was horrified by the emphasis of the Brethren only having the ‘Brothers’ preaching and teaching! Sadly, she talks about her ‘father and grandfather as ministering brothers in the most reclusive and savage Protestant sects in British history’.

For Rebecca, her use of Brethren language is remarkably classical. She uses the very words that I can remember hearing as a child. These were very different phrases to what you would normally hear in a church, such as ‘caught up in’, outside in the world it was ‘dangerous’ and where ‘Satan lived’. The Bible was the ‘Scriptures’.

Rebecca describes the fault lines between faith and doubt, duty and love. To her, doubt and love were in short supply within this sect. Then I remembered this quote by a Captain in a Roman legion in Libya: There are in life but two things to be sought, Love and Power, and no-one has both”.

It seems to me that Rebecca’s understanding of her Brethren past remains. To her, this is an area of her life that continues through to now. I suspect that this will not ever leave her.

See also: www.brethrenarchive.org

——————————————————————————————————————-

In the Days of Rain – A Daughter, A Father, A Cult

Rebecca Stott

394pp, 2018, 4th Estate

ISBN: 978-0-00-820919-3

——————————————————————————————————————-

An Advent Meditation

Still me Lord and calm me. You’ll be with me throughout today. I know it. Let peace rule in my heart. Let calmness rule in my soul. #Advent

Enfold me Lord. You love me and you’ll love me all through today. I know it. Let love rage in my heart. Let God rule in my soul. #Advent

Forgive me Lord and cleanse me. You’ll be with me throughout today. I know it. Let forgiveness rule in my soul. You are in my soul. #Advent

You Lord are Mystery. I cannot know you fully. Yet you’ll be with me throughout today. I know it. Let me awaken to your glory all around. #Advent

You Lord are my strength. You’ll be with me throughout today. You are my joy. Lord you are my life. You are my salvation. I know it. #Advent

The Lord is my Light and my Salvation – Jesus Christ is the Light of the World.

Review: The Church in Madras (Rev Frank Penny) 1904-12

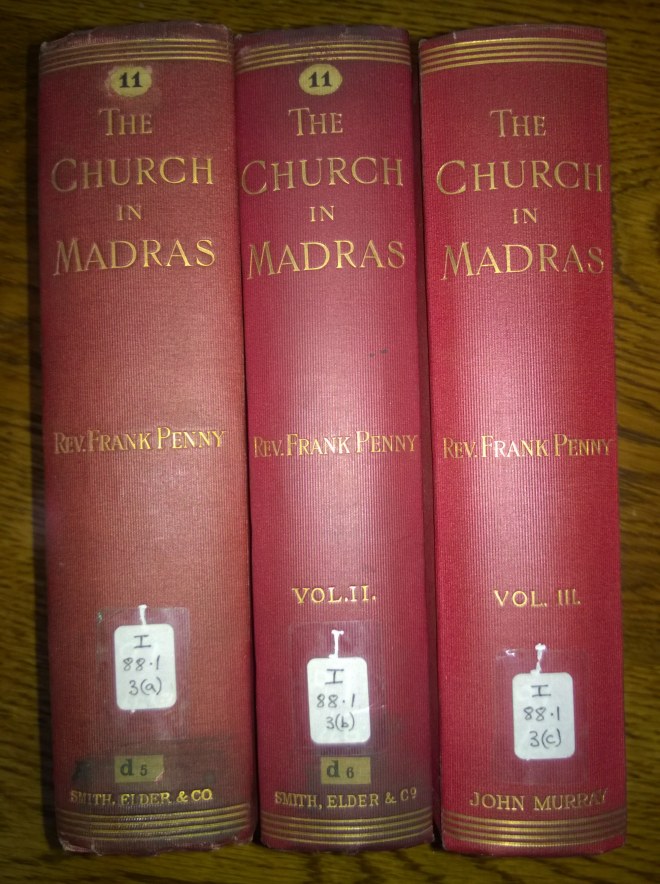

‘The Church in Madras’

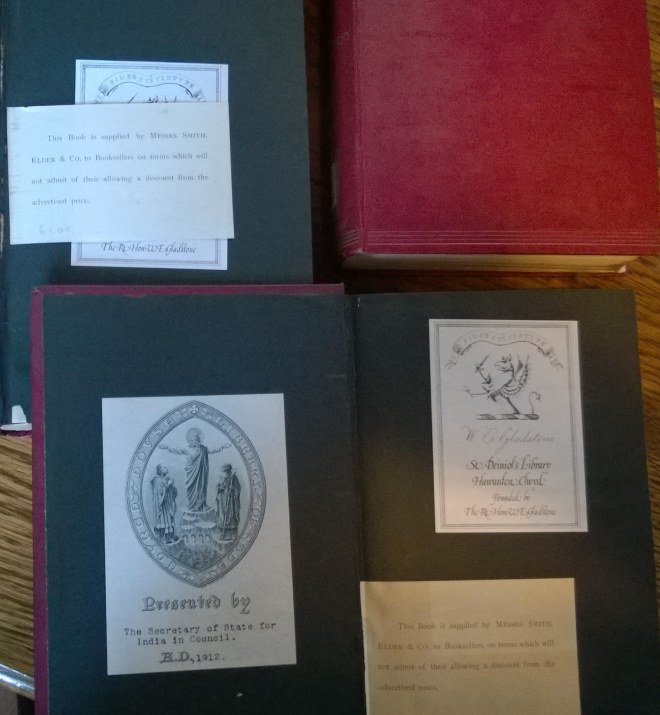

A 3-volume red hardback set (I.88.1) housed in Gladstone’s Library, Hawarden, Wales.

Written by Rev Frank Penny from 1904. Final volume published in 1912.

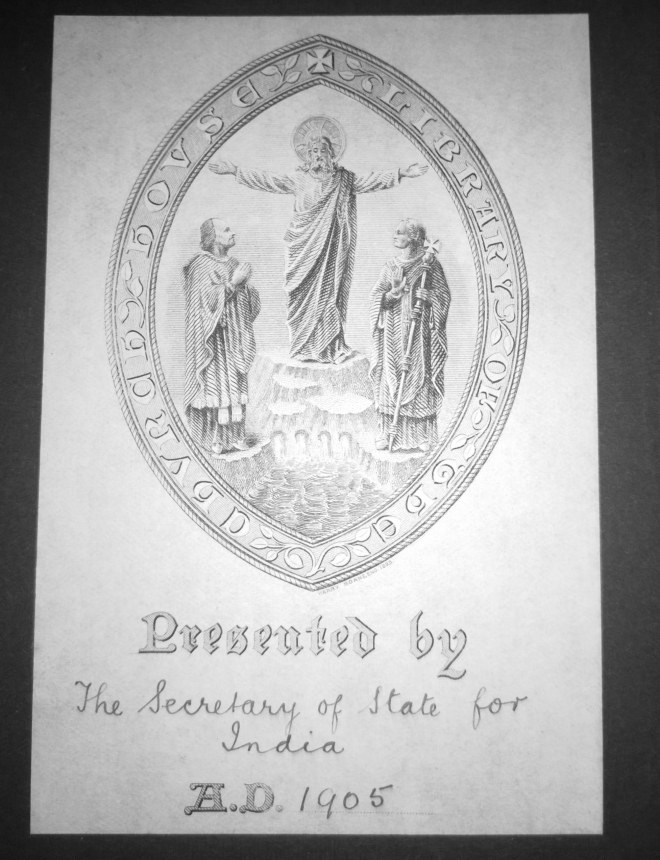

Frontispiece: Presented by the Secretary of State for India (1905, Vol 1-2), Presented by the Secretary of State for India in Council (1912, Vol 3).

Vol 1 1640 – 1805 Inc. St Mary’s, Madras, page 81

Vol 2 1805 – 1835 Inc. St Stephen’s, Ooty, page 320

Vol 3 1835 – 1861 Inc. All Saint’s, Coonoor, page 169

It was thrilling to see on page 196, the word ‘should’ written in pencil in the margin by William Gladstone replacing ‘shall’, proving that Gladstone himself read these volumes!

The East India Company (EIC)

The EIC was neutral about Christianity and its work, but their Charter of 1698 (renewed in 1792 by William Wilberforce) required them to employ Chaplains. These, in turn, had to be approved by the Bishop of London and had to be from the Protestant Communion.

However, the EIC officially discouraged and sometimes prevented the work of missionaries and Christian mission. The Royal Danish Mission and the SPCK (mostly Germans) worked in the south of India for the ‘Great principle of the duty of promoting Christian Knowledge’. There was therefore a marked difference between the work of the EIC Chaplains and that of the SPCK missionaries.

Fifteen Churches were built within the bounds of the Madras Presidency by the Company and six or eight more were built privately.

By 1835-61, 41 Churches had been built in India.

See also – Bishop Stephen Neill, ‘The History of Christianity in India’.

Travel: San Thome Basilica, Madras (now Chennai)

Just yards from the beach, south of Chennai, this Church is traditionally built near to or over the site where ‘Doubting’ Thomas, the Apostle to India, was reputedly martyred in AD72, having come to India in AD52.

This large white Roman Catholic Cathedral dates from 1896, and was given the status of Basilica in 1956.

It is one of only three churches worldwide said to contain the tomb of one of the twelve disciples of Jesus.

Marco Polo recorded a chapel on the seashore during his travels in Asia in 1293. The original small church was built by the Portuguese in 1523. The Prelates on this brass plaque in the Basilica date back to 1600.

Travel: All Saint’s Church, Coonoor, Tamil Nadu

Coonoor was one of three Hill stations established by the British Raj in the Nilgiri Hills in Southern India. Elevation 1720m.

The Church was dedicated in 1851 and opened in 1854. A distinctive cream-coloured English-style Church in India.

‘A charming and restful spot of great natural beauty’ (The Church in Madras).

My journal entry (October 2014):

‘After lunch, we visited All Saints Church, next door to the Gateway Heritage Hotel. This was quite a revelation – a beautiful interior, well looked after and clearly still well used. It has a dark wood, vaulted roof space, lots of stained glass and is well painted both inside and out. Someone opened up for us. So glad that he did. The large and reasonably well tended graveyard contained the usual poignant memorials to those who died in India – from the military, the church and the planter community. All far from home’

Travel: St Stephen’s Church, Ooty, Tamil Nadu, India

Ooty or Ootacamund in the Nilgiri Hills was one of three Hill stations in the area favoured by the British Raj. Elevation 2240m.

Ootacamund became the summer headquarters of the Madras Presidency, nicknamed ‘Snooty Ooty’.

The Church was dedicated in 1829, opened at Eastertide 1831 and is the oldest church in the Nilgiris.

It has a beautiful dark wooden ceiling with huge beams hauled by elephant, following the capture of the city palace of the conquered and feared enemy of the British, Tipu Sultan, in Seringapatam over 100km away.

My journal entry (October 2014):

‘We arrived at St Stephen’s Church, a cream-coloured, somewhat squat building dating from 1831. Climbing the steps, we entered the Church after first removing our shoes. It had a gorgeous dark wood interior with white paint and the usual array of brass memorial plaques. Outside, I wandered through yet another unkempt Anglican, colonial graveyard full of decaying tombs and headstones, now in the hands of CSI but utterly uncared for and overgrown. How many relatives know anything about any of these graves? There must be thousands of such spots all across India, gradually fading away into the past’.

Travel: St Mary’s Church, Fort George, Madras (now Chennai)

This is the first English Church built in India. It is the oldest English Church east of Suez.

Clive of India was married in the church, as was Elihu Yale, an early founder of Yale University.

The barracks were built in 1687 but St Mary’s was begun in 1678. It was consecrated (controversially) by Richard Portman in October 1680. The organ was installed in 1687. The spire was added in 1710.

The walls are 4ft thick, it was built to withstand siege and cyclone and had a blast-proof roof of solid masonry. The brickwork is 2ft thick.

The building could accommodate 500 people. The distinctive black granite baptismal font dates from 1680.

My journal entry (October 2014):

‘St Mary’s – the oldest English church east of the Suez. So many similarities with St Andrew’s cathedral in Singapore, just not as big. So many brass memorial plaques to those who died, often of sickness and disease, many very young. We strolled in the heat of the beautiful sunlit church garden. A peaceful place. Butterflies. Odd how a mercantile and mercenary Raj took the Church with it as part and parcel of Empire. It was obvious you would think, wasn’t it? Well, as the years have unfolded, no – it was a bad idea! Felt a little strange that Grandad would have known this church. Presumably as a bandsman, he may even have set foot inside. At the back of the building, I saw an old fading photo of George Town at the time (1905) he would have been there, so very different to today’s Chennai’.

The great Lutheran Pietist missionary, exemplar and intermediary, Christian Friedrich Schwartz (born 1726) arrived in India in 1750. He is remembered in India fondly and in the stirring epitaph at the base of the large white marble sculpture in St Mary’s (by John Bacon Jr, 1807).

Schwartz was truly the first Protestant missionary to India, not William Carey as often supposed. Carey arrived in India two years after Schwartz’s death at Tanjore in 1798. Schwartz died a rich man but he left all his wealth to the SPCK for its work in India.

Recent Comments